With a voice clear and resolute, Makui Lainyiu filled her simple home with with the music of loss. Her lament to the corrosion of Naga culture has been sung around cooking hearths for many years — but has rarely if ever been heard outside this region. The lyrics say more than many people here had dared to utter publicly during decades of military rule.

Makui Lainyiu views the decline in Naga culture with a pragmatic acceptance, acknowledging that she herself could have done more to pass traditions on to her seven grandchildren. But her young granddaughters were clearly spellbound listening to the stories of her life, many of which they had never heard before.

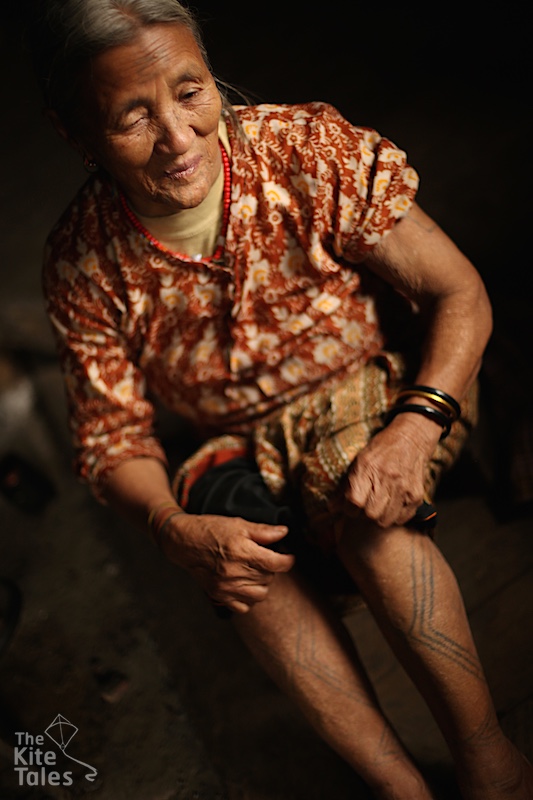

“I’m very proud of my tattoos, I think I’m very beautiful because of them. I also think you’re very beautiful while dancing when you have tattoos. I have plenty of bracelets too and I used to put them all on, stacked high up my arms, before going dancing. I don’t have any photos of those days. I’d wear my bracelets and necklaces even when I was pounding rice.

“I used to be a tattoo artist, though I can’t remember the designs I tattooed on other people. In the past, it was the tradition that women would have tattoos and it was considered beautiful for girls to have face tattoos. That’s why we did it.

“We didn’t tattoo the whole face though, girls shouldn’t do that. Only men would tattoo their necks and face.

“If you want to get a tattoo outside of (special ceremony) days then you have to hold a big reception for the tattoo artists and provide them with food and stuff. I used to tattoo other people on these special occasions. Both men and women.

“It’s a really sharp pain and it bleeds. But people don’t cry, they’d bear the pain to get the tattoo. They would have to go through it again and again if the design isn’t clearly visible.

“I was quite young when I had the one on my face done. I got the one on my feet when I got older, just before I got married. I also have some on my arms.

“The reason why I had a face tattoo at a young age was because (my parents) were worried a Bamar man would marry me. Previously, we were very afraid of Bamar people. When they came we would just run away. We were also banned from marrying Bamars, we were told to only marry our own races.

“When the (government) forbade us from getting tattoos, I stopped being a tattoo artist and also stopped getting more done. Both the tattoo artist and the customer were punished in order to put an end to this practice. That’s how it died out.

“The traditional festivals have changed and only some people hold them nowadays. I don’t necessarily feel sad about it. I haven’t really taught the younger generation about these traditions either and I don’t want to start now. I can’t work or talk very much anymore.

She indicated her granddaughters: “When they are educated I want them to become teachers or nurses. If they have education I don’t want them to work in the field. We don’t make them do any farm work now either because they’re studying.

“When I was young, my parents didn’t let me go to school. They just made me work in the farm. It’s good (that this has changed). I would have wanted to go to school if I was allowed to go, like girls are today.

“There’s no one left here of my age now — I must be about a hundred years old.

“I used to go to Hkamti (a three day walk away) to dance at the festivals. All the people that I travelled with in those days have since passed away.

“But I’ve only been as far as that. I was once offered a trip in a helicopter but I was too scared, so I didn’t go. If they asked me now I’d say yes.”

(Interviewed April 2016)