The Ludu Library is a rare literary treasure trove in a nation still reeling from the oppression of army rule. Tucked down a modest alley, away from the frenetic bustle of the city, it is one of the very few modern libraries in the country.

It was built to house the books and manuscripts accumulated over the lifetimes of Myanmar’s most famous literary couple, Ludu U Hla (1910-1982) and his wife Ludu Daw Amar (1915-2008) who founded the left-leaning “Ludu” (The People) newspaper in 1945. The couple’s writings put them at loggerheads with successive governments and they were frequently harassed and imprisoned, along with other members of the family.

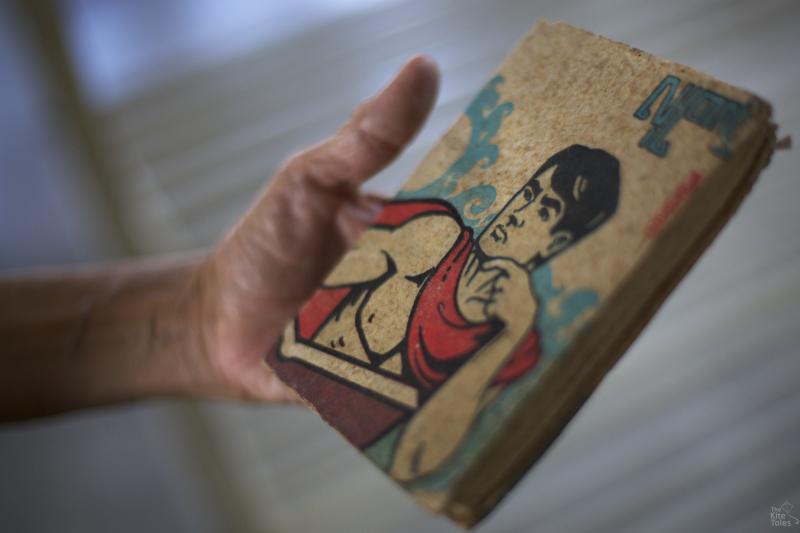

Their books survived army rule, fire, and the annual onslaught of the monsoon. They are now looked after by their daughter Than Yin Mar, a doctor, author and retired medical professor, who has overseen the library for more than a decade.

“This library is the precious thing for our family, for my family. This is for this nation,” said Than Yin Mar, who has overseen an ambitious digitisation programme to preserve the Ludu journal and other newspapers and rare books.

“Although it’s now the internet age and people are used to read from the e-libraries, in Myanmar they still use books to read. And I see so many younger (people) come and read in this library and it’s still very useful. And above all we love to have a newer generation who love books. And from this they can make their aims and their dreams come true.

“My parents Ludu U Hla and Ludu Daw Amar they collected books in all their lives. Old newspapers, books. And they had a collection of books which are autographed by friends. We still have those books.

“They collected all those books in their house in iron boxes. And my father used to dry them in the sun once or twice a year so that it won’t be eaten by the insects or destroyed.

“They both thought that these collections of old newspapers from the early colonial period and the whole collection might be useful to the newer generation, where they use as references to write for history, for literature and for the librarian courses.

“My father and my mother they were workaholics. I never saw them sleeping on the bed, or listening to music they didn’t have leisure time they just sat down and wrote all the time.

“When they were doing newspapers, they worked until very late in the night. My father slept when the newspaper came out, about four in the morning. He wanted to see — is it alright?

“(My father) wrote a book known as ‘Lower Burma’. My mother published that book when he died. The references were all from the old newspapers which he collected. And he wrote about Burma during World War Two, Burma after World War Two.

“We are very lucky that (the collection) wasn’t abolished by the fire that broke out in 1984, known as U Kya Gyi fire that abolished almost one third of Mandalay. It did destroyed the press and the bookstores. Only our house was left and our books.”

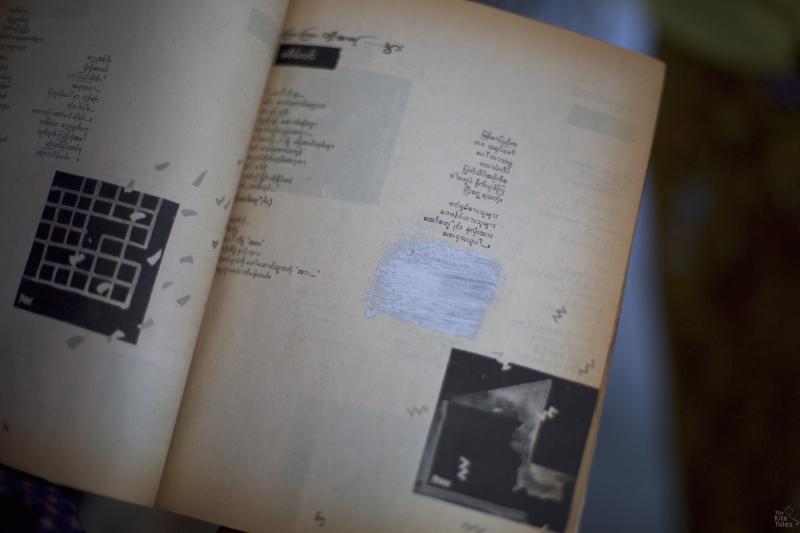

Many books in the collection bear the marks of the military’s draconian censorship regime, which required novels, newspapers and even song lyrics to be submitted for pre-publication scrutiny. Draft manuscripts are slashed with red ink and scrawled with orders from censors to change or omit passages. Even after publication, texts were not safe from the editorial incursions of military officials. They used silver paint to block out text and would sometimes stick whole pages together to stop their content from reaching the public. While the censorship law was changed in 2012, Myanmar continues to lag on press freedoms.

Previous government rules would have effectively forced the family to hand the collection to the authorities. And while these have recently been modified, the family have decided to retain the library’s independence.

“I think it will never be a public library. Even though this government has changed and the rules and regulations of libraries are going to be changed, I think it is better to be a reference library so we can make the collection more safe.”

Than Yin Mar blinked back tears as she spoke of her parents’ passion for literature and preserving their collection for future generations.

“They would be very happy and satisfied that their children and the third generation are doing their best to preserve their collections and make them very helpful for this nation. It was their vision, that was their dream,” she said. Of all her siblings, she was the only one able to look after the books and run the library.

“The eldest son didn’t live very long, he died at the age of 27 years in the jungle. He was killed there because he had to run away from school and from home in the student movement.

“(And) my younger brother is also not home. He had to run away in 1975 and he was still in China, so it was my duty.

“I was retired in 2003 and I was working since then in this library. I was working as a caretaker of this library, for the cleanliness, for the garden.”

She was never tempted to follow her parents and brothers into a literary life, instead going into medicine.

“I was very happy to be a medical doctor because I could help so many people in this region.

“I am not bookish!” she said laughing.

“But we grew up in a house filled with books and journals.

“My favourite books were near my bed. They were written by my parents, my son, my friends and I used to collect poems by my friends. I read them when I miss them.”

(Interviewed September 2016)