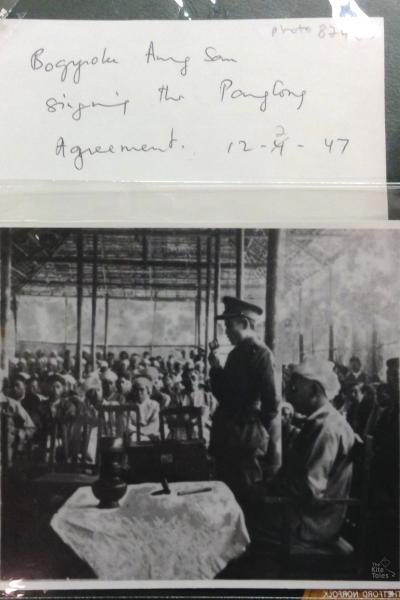

San Aung laughs easily but breathes with difficulty. At 93, the frail veteran journalist has no trouble remembering his greatest scoop; the time when he was the only accredited reporter to witness one of the most momentous events in Myanmar’s living memory — the 1947 Panglong Conference.

For many people in Myanmar, this meeting in the remote Shan village of Panglong represents the last great moment of hope for inter-ethnic harmony in Myanmar until Aung San Suu Kyi’s election ended military rule nearly 70 years later. The conference brought together her father Aung San — an ethnic Bamar who led the independence movement — with representatives of several minorities (Chin, Kachin, Shan) as the country stood on the cusp of freedom from colonial rule.

But the hope of peace and federalism that the agreement promised was never realised. Crucially there were some significant absentees, including the Karen who went on to wage the world’s longest civil war against successive Myanmar regimes. Even before independence was achieved, several uprisings swept the country and Aung San was gunned down by political rivals along with much of his cabinet.

Military strongman Ne Win cited the conflicts to justify his 1962 power grab. Decades of oppression, isolation and conflict followed and left the country with a legacy of distrust and poverty, particularly in the horseshoe of ethnic minority border regions.

San Aung jabs the air with glee as he tells us about his near-eight decade love affair with the news. The son of a police officer and a teacher, he was born and raised in the bustling city of Taunggyi, high in the Shan hills. He became a cub reporter as a teenager while studying in Myingyan - a district in Mandalay. When he returned to Shan State he was hooked on his new vocation, making sure that news from his part of Shan reached the distant presses of the national papers.

Forced away from reporting after the coup, he spent years under surveillance with periods of virtual house arrest.

He had stints working in a factory and as an MP, but he is still proud to call himself a journalist.

Tucked up in his bed wearing a Manchester United sweatshirt that looks as if it had been borrowed from a broader-framed relative, he is eager to tell his story. And there was a poignancy to our meeting. We had travelled to Taunggyi the day before hoping to speak to the the former mayor of the city, U Khan, who had driven Aung San to Panglong. Sadly he had died that morning.

“I want people to know about my experiences, just like I remember them. Otherwise my stories will be forgotten and lost forever. I'm at a point in my life where I'm essentially just counting down the days.

“My friend (U Khan) took his stories with him to his grave. I was just thinking about that and then you turned up this morning! My wish has come true. After all, there aren't many people around anymore who know the things I do.

“Being a journalist was really a passion of mine, nothing else came close.”

In 1939 at the age of 15 San Aung went to live with his police inspector uncle in Myinchan, central Burma while studying at a local school.

“In the evenings I would always overhear police officers coming to present my uncle with their crime reports whilst I was studying. I found it fascinating.

“I had an epiphany that I could write about these cases for the newspapers. So I tried my hand at writing some news stories based on the legal case reports that my uncle had received and dispatched them to the paper's (Myanma Ahlin) headquarters. To my surprise they ran what I had sent, mentioning me as an honorary journalist.

“Seeing my name in print really gave me the journalism bug. Before long a package arrived for me from senior management at the newspaper. They'd sent me some paper, bags and a press badge, instructing me to send them news via the telegram office should anything important happen. They told me that if I showed the telegram office my badge, I wouldn't need to pay to send the telegraphs, that it would be subsidised by the newspaper.

“They sent me money for my stories and, knowing I was a student, they also sent me books to help me with my studies.

“It was the beginning of my life as a journalist.”

Sang Aung dropped out of school during World War II “to report on the war which had enveloped my country”. The Japanese invasion and desperate battles with Britain and its Allies put what was then called Burma on the front lines of the conflict.

In the aftermath of the fighting, as the country grappled with devastation, talk independence from British colonial rule grew.

San Aung said he received a leaked letter that intensified discussion about whether the Shan States would be part of a future independent Burma.

“At the time, I worked in the Shan State People’s Freedom League’s (SSPFL) office on a voluntary basis, not taking on an official position because doing so would restrict my freedom. I wrote news, slept in the newsroom and helped out around the league's office.

“I was always heading off downtown to report on what was going on and would end up at the government’s Deputy Commissioner’s Office. After all, we were still under British administration. A man who I knew worked as a chief clerk there.

“One day he called me into his office and held up a document that was to be presented at Panglong. It said Burma proper would be granted independence, but the frontier areas of the country, mountainous regions such as Shan State, would not. They would remain as a British dominion. A copy was clandestinely leaked to me.

“It was decided that efforts must be made to inform General Aung San about this great secret,” he said, adding that after a messenger was dispatched with the document to Yangon, Aung San visited Shan State to meet some of the royal leaders, the Saophas.

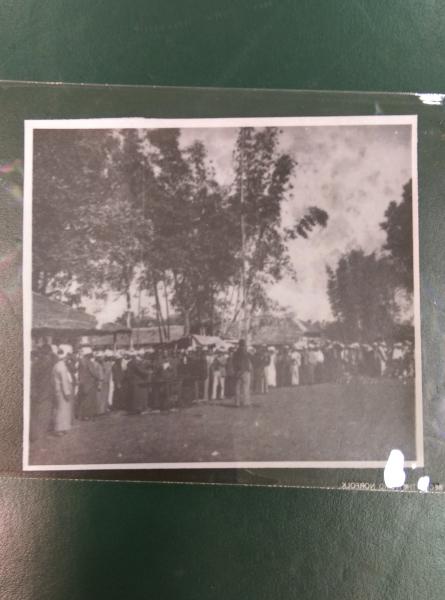

Aung San wanted them to recognise him as their envoy during his upcoming meetings with the British government in London, but the Saophas demurred, saying that not all of the Shan leadership had agreed. Later, Aung San sent a telegram directly to the leader of the SSPFL, a group loyal to his independence vision, asking for a show of support. This they duly provided, with a huge public gathering in Taunggyi. A telegram was then sent to London saying Aung San had the Shan people’s support.

This opened the way for him to be invited to the Panglong conference the next year.

“That was how, because of of General Aung San’s patience and political tact, together with his good fortune, Panglong became what it did,” said San Aung.

“A large stage was erected in the ceremony hall at Panglong, and the place was packed full of representatives, Shan Saophas, civil servants and regional representatives.

“Everybody knew that I was a journalist. The British army set up a telegram office at the Panglong Conference, forwarding to my newspaper the stories that I reported. I felt nervous, like a hunter searching for its prey, but I was happy. I was quite free to report on what I wanted.

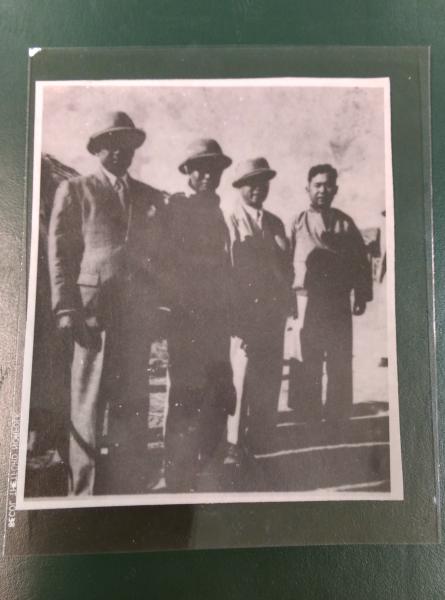

“I was sat directly in front of where the documents were signed. I had a camera to take photographs but it was of poor quality; it was just a simple box camera.

“I tried hard to focus on getting some good shots. I had a reel of film which allowed me to take just 12 photos.

“Despite practicing with the camera beforehand, I still had misgivings as to whether the photos were actually going to turn out properly.

“I’d made sure to set the lighting right. I clicked the shutter and heard the crunch of the camera meaning I successfully taken a photo. Everything seemed fine. The camera crunched and churned every time I took a shot.

“Finishing off the reel of film, I rushed back to the place I was staying, covered myself with a blanket and developed the film.”

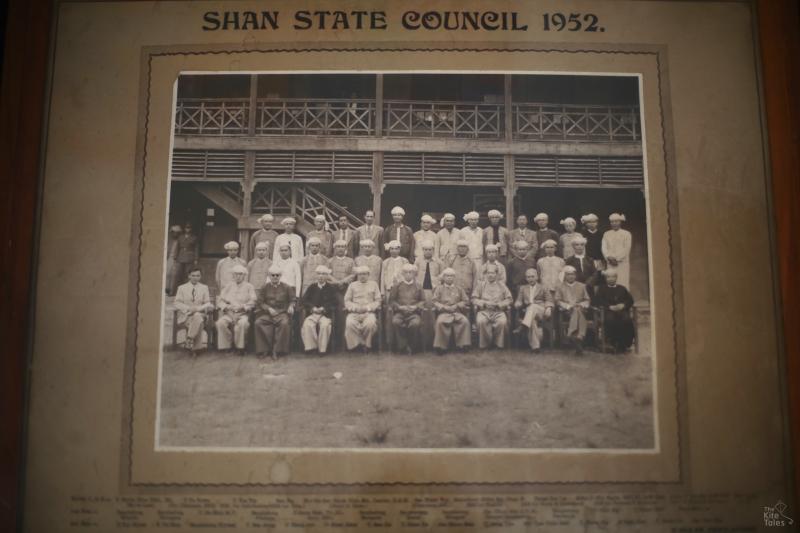

San Aung continued his reporting career after that historic meeting, publishing a newspaper in Shan State named after a royal practice of erecting a post where people could stand and speak of their grievances so that the king might hear.

“It was a short lived venture: we only managed to publish four issues before we had to flee after charges were pressed against us,” he said, referring to the first of many brushes with authorities.

Myanmar’s fledgling civilian government was struggling to contain ethnic tensions and civil unrest.

At one point Kayin insurgents occupied Taunggyi.

“I needed to disguise my true identity during that time. Luckily, a doctor at Taunggyi hospital was friendly with my uncle so I went to ask him for help, telling him it was dangerous for me to remain in the town. He was sympathetic and let me stay in the hospital where I pretended to be an inpatient. I spent three months in the hospital.”

As journalism became harder a new opportunity arose. He had become close to ethnic Pa-O insurgents during his reporting and their leader Hla Pe urged him to take up a seat in parliament on their behalf.

“I was taken aback. It wasn't a role befitting a journalist like myself; I couldn't do it. But he ordered me not to associate myself with them any longer if I didn't wish to help. So I subsequently accepted and became a member of parliament representing the Pa-O. I attended parliament until 1956 representing the constituency of Yatsawk.

“I worked in other capacities in my life but always as a volunteer. I knew that if I took up any position, it would be the death of my career as a journalist.

“To this day, I'm still a journalist, and I will be up until the day I die.

“Freedom is what I value most in life. I love being a journalist and the freedom that comes with it. I didn't want to be anything else. Freedom of expression is very valuable. It's imperative that the public are educated about its importance.”

(Interviewed June 2016. San Aung died on January 31, 2017)