One of the very first things the Myanmar military did when it staged its coup in the early hours of Feb 1, 2021 - just before a newly elected civilian government was due to take office - was to cut off communication networks across the country. The initial shutdown lasted hours, but would only mark the beginning of years of targeted blackouts and internet censorship.

In the weeks that followed, the junta continued to dismantle the infrastructure that allowed people to stay informed. Websites and social media platforms were blocked. News outlets were banned. Newsrooms were raided. Journalists were arrested when they could be found, and equipment was confiscated.

Myanmar’s lively and hard‑won media ecosystem went underground almost overnight. Hundreds of journalists fled their homes, working from safehouses, with many eventually crossing into Thailand or reporting from rebel-controlled territory. Many more lost their jobs. Being a journalist became synonymous with being a criminal. Some were even charged with terrorism.

And yet the reporting never stopped.

Newsrooms regrouped wherever they could, with whoever they had left. They continued publishing, broadcasting, documenting atrocities, and explaining - often at great personal risk - what was happening to their communities.

Journalism has long been in the crosshairs of Myanmar’s governments, democratic or otherwise. But the military has always been the biggest foe and most dangerous adversary. It is perhaps unsurprising that a murderous, corrupt, unaccountable, sexist, and xenophobic institution would find scrutiny intolerable.

What is much, much harder to digest is that the junta may finally succeed in silencing Myanmar’s independent media in a way it has not previously been able to, because of Western geopolitical drift, shifting ideologies, and myopia.

Essentially, Western governments that once championed a free press as a cornerstone of democracy have largely turned away, at precisely the moment their support is most needed.

Myanmar, Now

The first domino to fall was USAID. In early 2025, funding cuts under the new Trump administration crippled many Myanmar newsrooms that were already operating in exile and on shoestring budgets. Then in September, Sweden, the other major donor, announced it will end its support of Myanmar media from 2026 onwards.

The blows kept coming. In recent months, at least one other European donor quietly informed smaller, regional outlets that its funding would also be ending.

This could not come at a worse time. The crisis has faded from much of the world’s attention, but the junta’s violence has not diminished. It has continued to terrorise its own people, a vast majority of them unarmed and innocent. At the same time, the regime is finding more acceptance in the international community. Sham elections organised by the military and pushed by China appear to be leading to a thawing in Myanmar’s relations with its neighbours.

Away from international attention, things continued to worsen in Myanmar. A nationwide rebellion sparked by the coup has deepened long-running conflicts, and pushed the economy into collapse. In the ensuing chaos, corruption and lawlessness have flourished, with global spillovers ranging from online scam centres, drug production, to unregulated rare-earth mining.

I bristle every time I hear Myanmar journalists described as “resilient.” It is a word that has become a polite substitute for abandonment. Resilience should not mean being left to survive indefinitely without resources, safety, or pay, but this is what many have been doing over the past five years.

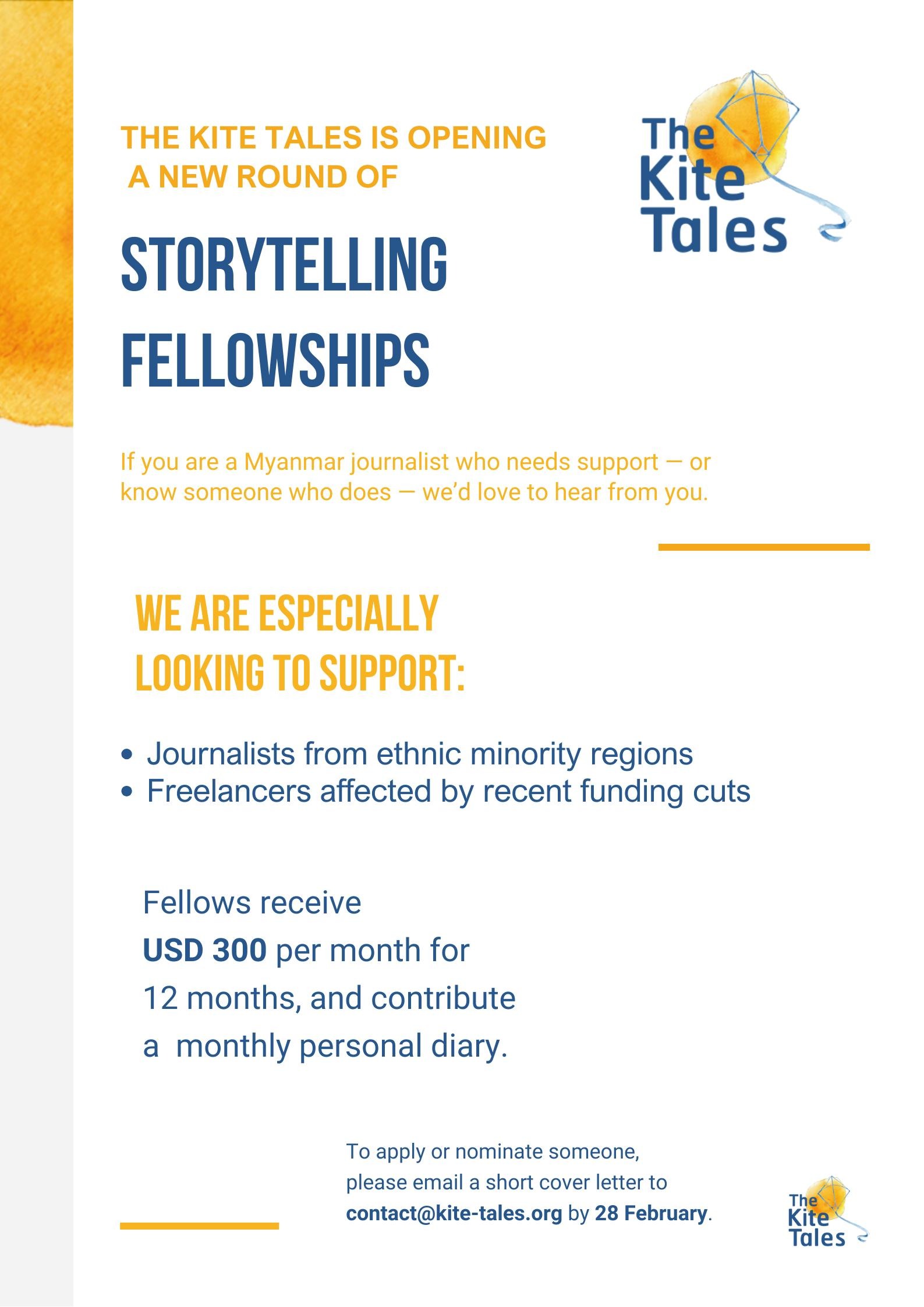

The Kite Tales, a non-profit storytelling project I co-founded, has been supporting journalists and illustrators both inside and outside of Myanmar. We provide them with a small stipend for a year and they provide us with vivid accounts of what life is like in a country under siege, and why they do what they do.

This support does not replace traditional journalism work. It’s about providing a modest but vital income boost that allows journalists to keep reporting, because let’s face it, courage and commitment don’t pay rent.

They report on airstrikes, food insecurity, prisons, displacement and a dozen other daily realities. They write about families, histories, heartbreaks, and futures tied to Myanmar’s fate. We publish them as “Resistance Diaries”.

Many have suffered personal losses: a home during one of the worst earthquakes to hit Myanmar in recent history, a baby due to work and personal stress, or freedom during months in prison.

Yet they never stopped reporting about the people of Myanmar: a youth who dreams of setting up his own small business, a former traffic cop who joined the resistance, or a boxer seeking justice.

For many journalists, the emotional burden of covering the junta’s atrocities, which include mass killings, lingers long after deadlines.

Describing the April 2023 airstrike on Pazi Gyi village, one says it was “the worst day of my life… My heart couldn’t bear it. I felt completely disoriented.” But her diary also captures the survivor’s guilt that many exile journalists feel.

“If I feel this way, imagine the depth of suffering felt by the women and children who directly experienced these events,” she wrote.

Another reporter describes it this way: “Compared to the worsening crisis in my country, my financial struggles seem trivial.”

He is one of the many reporters whose lives were first upended by the coup and later by the USAID cuts.

“Last year my newsroom secured money from the United States that meant I could finally begin planning to reunite with my mother. Then Donald Trump began slashing support for independent media and all my dreams unravelled.”

The Wonder Years

There have not been many opportunities in my lifetime to tell hopeful stories about Myanmar. But there was a brief, imperfect opening, and I remember it vividly.

It was Nov 13, 2011, and I was standing in a sterile, air‑conditioned press room at a conference centre in Bangkok when the rumours started: Daw Aung San Suu Kyi might be released from house arrest. The television was tuned to rolling coverage from Yangon. Like everyone else, I stood transfixed in front of the screen.

For most of the journalists there, it was simply the biggest breaking news story of the day. For me - likely the only Burmese person in the room - it was intensely personal.

You see, the cameras were trained on University Avenue. That was the street I grew up on, among extended family, in a leafy compound with swings on the front lawn, my mother’s anthurium plants in the back garden, and a constant stream of relatives and visitors. Just up the road, at number 54, lived Daw Khin Kyi - the widow of Myanmar’s independence hero Aung San - and after 1988, her daughter, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

Politics had always murmured in the background, but until 1988 I did not fully grasp that I was living in an isolated military dictatorship. The years that followed saw multiple crackdowns against unarmed protesters, regular roadblocks on my street, and military intelligence moving into nearby buildings to monitor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The neighbourhood fell silent at night. I left the country a decade later to study.

For years my family forbade me to return, even for funerals, after a sibling’s passport was confiscated upon arrival. Like so many families, ours stretched across continents, held together by phone calls and longing.

My parents had hoped I would become a business executive. Instead, I chose journalism, a decision that alarmed them deeply. To them, being Burmese, a woman, and a journalist did not conjure images of press conferences, but of prison cells.

I clung to my crimson Myanmar passport nonetheless. It is an inconvenient document - onerous visa requirements almost everywhere, suspicion at borders - but it allowed me to return undercover when Cyclone Nargis devastated the country in 2008.

In 2015, 10 months before the historic elections that would usher in the first democratically-elected government in half a century, I returned home properly. I helped set up Myanmar Now, and later Kite Tales, and voted for the first time in my life.

There was genuine hope. Journalism flourished. Young reporters asked hard questions, often for pitiful pay, sometimes facing attacks even from civilian leaders. The period was imperfect - the Rohingya crisis and the rise of xenophobic nationalism remain a deep stain - but the press persisted.

What Disappears When Journalism Does

Today, that ecosystem is on the brink.

I was recently speaking with journalists at an international investigative conference when it hit me how many of the newsrooms I have been working with over the past three years are barely hanging on. Reporters from Kachin, Shan, Rakhine, Tanintharyi, Yangon, central Myanmar, the delta - all are still reporting, but utterly exhausted.

Revenue streams have collapsed. Advertising is impossible. Subscription models are a fantasy in a country at war. And yet donors increasingly insist on “self‑sustainability.”

Even the most storied news organisations in the West are under persistent financial pressure that raises questions about their future viability. The Guardian is owned by a trust intended to protect editorial independence, and legacy outlets like the Los Angeles Times and Washington Post are backed by billionaires precisely because commercial advertising can no longer sustain serious reporting.

The New York Times has diversified revenue aggressively - but still depends on subscriptions, corporate partnerships, and philanthropy to fund investigative work that rarely turns a profit.

In that context, insisting that exiled newsrooms operating under constant threat while covering a war-torn country become “self-sufficient” within a few years isn’t just unrealistic but also frankly unreasonable.

Journalism is not a luxury. In Myanmar, it is service journalism: tracking airstrikes, documenting land grabs, monitoring armed groups, explaining conscription orders, recording who has disappeared.

Through Kite Tales, we have been fortunate. Two private organisations have committed support through 2026 and friends have sent funds too (thank you so much, you know who you are!!!!). We keep overheads minimal: the founders volunteer their time, the board of trustees provides precious advice for free, and around 95% of our spending goes directly to fellows.

This funding means we will be able to support 10 storytellers, including eight new journalists, throughout 2026. We are committed to ensuring there is gender balance and ethnic diversity and we want to prioritise freelancers who are currently operating without any safety net. If you know talented journalists who could benefit from this kind of support - or organisations that might partner with us - we urge you to get in touch.

But this is a drop in the ocean.

This is not about supporting one organisation. It is about an entire information ecosystem. Even in the depths of the old military regime, there was a spirited exiled media scene. Now even that is imperilled.

We already see what a cowed media landscape does elsewhere. In Myanmar, where accurate reporting has largely been silenced inside the borders, the stakes are immediate and human. This is about people’s ability to live with dignity, to know what is happening to them, to be seen.

Five years on, the darkness has not lifted. But neither has the determination of those still telling Myanmar’s stories.

They should not be left to do it alone.

Thin Lei Win

Jan 30, 2026